Hayley Mills

She was twelve years old. And she had been awake all night pondering her future.

Ever since she was a very little girl, friends of her daddy used to pick her up on their laps—and say:

“And what are you going to be when you grow up?” Her answer was alway the same.

“I’m going to be a mother when I grow up.” “And that’s all?” “That’s all.” But the night before she wondered whether that was all she wanted to be—really.

For Hayley, the baby daughter of top British star John Mills and Mary Hayley Bell Mills had grown up in a world that was a mixture of the brightest literary and theatrical circles—and the quietness and quaintness of the old English countryside.

Her god-parents were among the most famous figures in the world.

And when “Uncle Larry” (Olivier) would visit the farm, he’d take her piggy-back riding.

And “Uncle Noel” (Coward) would send her pretty toys from all over the world.

But in the morning—way before breakfast, she’d run down to the barn, feed the baby colts, and in watching them with Peers learn the marvels and mysteries of life.

AND HER HEART WOULD ACHE with the longing to grow up fast, so she too could have babies all her own.

Her sister Juliet, four years her senior, wasn’t in that much hurry to grow up.

At sixteen, Juliet was an experienced actress: one who had been on the stage periodically since she was a baby.

And although Hayley had seen her father in movies and on the stage and thought he was “quite wonderful,” she couldn’t understand her sister’s preoccupation with all “that make-believe stuff,” or how she could have the patience to be locked up in her room with a script, when she could spend that same time riding over the countryside, or taking care of the vegetable garden, or playing with the animals.

Then—suddenly, the night before, a big change came over her.

A friend of daddy’s, director J. LeeThompson came to spend the weekend and confer with John about the script of their new movie together, Tiger Bay.

They were talking about it at dinner.

“We can roll tomorrow,” he said, “if we can get the proper child. But we’ve tested two dozen and can’t find one that’s just right.

“We want someone fresh and beguiling—and without precocious mannerisms . . . Someone like . . . well, someone like your little Hayley.”

Hayley played with her potatoes and roast beef, and as he kept talking, her eyes grew wider and wider.

Then she went to her room and “thought and thought and thought.”

At 6 A.M. she went down to the barn— “and thought some more.”

By the time she went in for breakfast—she had made up her mind.

She still wanted to be “a mother” when she grew up, but she also wanted to be an actress.

She asked Daddy about it at breakfast.

“I want to be Gillie, Daddy. I know I can do it. Honest I can. If you’ll let me.”

“Are you sure, Hayley?” Mills asked. “It’s a lot of hard work. And it means giving up your summer vacation and going to bed early every night and learning lots of lines.”

“I’m sure, Daddy.”

Mills was apprehensive. After breakfast he discussed it with Thompson.

“Do you want to take a chance with a completely inexperienced child?” he asked. “I never even knew Hayley wanted to act—and frankly Lee, I don’t know if she can.”

“Well, she has the quality and the charm. I’ll take the chance—if it’s all right with you. After all you’re the star of the picture.”

After two weeks of shooting, John told his friend: “Well, I was the star of this picture. From here on in, I’m just a supporting player.”

HE MADE THE SAME CONFESSION to his daughter:

“Hayley, when this picture is released, no one will even know I am in it. I can see the reviews now. They are going to say that you are the greatest child actress in twenty-five years.”

“Oh Daddy, do you really think so?”

“I don’t think so . . . I know so.”

‘ The picture ended almost too soon for her.

And then it was time to return to school.

“But Daddy,” she said. “I want to act ever so badly. Do you think I will soon again.”

“Again, Hayley, but not soon. Not until next summer.”

“But next summer is so far away. I should be forgotten by then.”

“I promise you will not be forgotten, once this picture is seen.”

She returned to classes at the Angelo Catholic school, where her sister had attended before her.

She wished that Juliet was still there so she could share her feelings and her delicious anticipation with her.

There had only been one year in which she and Juliet had been at the school together: her first and Juliet’s last—and it was the most wonderful fun of all.

She had lots of other friends—but somehow she couldn’t tell them about it.

They would ask: “What did you do this summer, Hayley,’ and she would answer, not untruthfully, “Oh . . . I played.”

She never mentioned the picture to anyone.

She concentrated on her school work, and daydreamed only a little about next summer.

And then suddenly Tiger Bay was ready to be premiered in London.

Mills wrote Father John, the padre of the school and made arrangements for Hayley to get off to come to London for a few days.

Mary and John opened the London flat, and made a real holiday of it. It was especially wonderful because it meant a reunion with Juliet who was then appearing on the London stage in Five Finger Exercise.

There was a new party dress and a dinner celebration and all the trimmings, but she still went through the evening in some kind of a daze.

The applause at the end of the picture was real enough.

So was daddy’s, “You’re a star, darling.”

But she still couldn’t believe it.

She spent another sleepless night—her first since making the “big decision.”

And she got up at seven in the morning to wait for the paper boy.

The rest of the Mills family were sleeping soundly as she turned from one drama page to another.

HER HEART JUMPED at her reviews. The marvelous praise—the lines and lines and lines written about her.

Then her heart sank.

For in their overwhelming praise and enchantment of Hayley, John Mills was all but forgotten.

She heard stirring in the other room and hurriedly gathered up all the papers and hid them under a chair cushion.

Mills came out from his bedroom.

“Up so early, Hayley. After all that excitement I thought you’d sleep until noon.”

“Oh, I wasn’t very sleepy.”

John looked around the room, and outside the flat.

“Hmmm . . . the papers should be here by now. Wonder what’s delaying them. I’m anxious to see the notices. Aren’t you?”

Hayley became terribly absorbed with some specks of dust which had gathered on the coffee table.

“Well, let’s go to breakfast. Starving?”

“Yes, Daddy.”

Throughout breakfast Mills got up to see if the paper boy had arrived.

“Can’t understand it,” he muttered. “On this of all mornings, the delivery should be so late.”

Hayley became terribly absorbed with a speck at the bottom of her glass of milk.

After breakfast they returned to the living room.

Mills sat down on the big easy chair—which this morning wasn’t easy to sit on at all.

He pulled up the cushion and saw all the papers piled beneath it . . . turned to the cinema pages.

“Hayley!”

“Yes, Daddy.”

“Why didn’t you tell me the papers had arrived and you read them.”

“I’m sorry, Daddy. But I’m afraid they are all about me. And . . . and, well I didn’t want your feelings to be hurt.”

“Hurt? Hayley, I’m delighted. I told you they wouldn’t know I was in the picture. And you see—it says right here that you are the greatest child discovery in twenty-five years. I’m very, very proud of you.”

When she returned to school, her secret was no secret any longer.

Word had spread like wild-fire about her performance in Tiger Bay, but what amazed the faculty and her school-mates was her ability to keep silent about it— and how totally unaffected she was by her success and her wide spreading fame.

Because within weeks her fame was spreading—far and wide.

Tiger Bay was submitted as an entry in the Berlin Film Festival and she copped The Golden Bear Award for the best performance of the year.

Disney saw the picture—and knew that his long long search for an actress to star in Pollyanna was at its end.

He discussed the possibility of placing her under a long term contract to him with John Mills.

“THIS IS WHAT HAYLEY WANTS,” said Mills, “and I won’t stand in her way—but her education comes first.

“We’re doing our utmost to keep Hayley just the way she is. We want to be proud of her in every way, not just for whatever she accomplishes in her career.”

Disney understood.

A compromise was made.

Hayley would do one picture for him every year while she is still a schoolgirl— and he would try to arrange the schedule to fit in with her summer vacation. The rest of the time she would remain in England. But could some arrangement be made for Pollyanna—which would of necessity run into the school term?

Mills contacted Father John, who immediately replied:

“We realize that Hayley is one of the exceptions of this life and we are prepared to welcome her back here whenever she can get to us.”

So Hayley and Mary Mills went to Hollywood, together with ten-year-old Jonathan.

John remained in England for a movie.

Juliet went off on her own to Broadway for the New York production of Five Finger Exercise.

The family was separated—but only in a physical sense.

Each day Hayley wrote her father—and her sister.

Particularly her sister. And there was so much to write of the wonders of California:

“Oh my dear!” she’d exclaim. “It’s simply marvelous. The hamburgers—and the roast beef which is an inch thick and not at all like the roast beef at home which is so thin.” (“Oh, my dear” is an expression Hayley has picked up and sprinkles in all her correspondence.)

She’d write of the new friends she had made, and of the odd studio school—which was classes in a trailer, and of the marvelous clothes she had seen and bought.

“And, oh, my dear,” she’d write, “have you heard Elvis Presley’s latest recording? It is smashing.”

For at thirteen, Hayley fell smashingly in love with Elvis Presley.

Boys as boys were unimportant to her. She felt herself much too young for such nonsense.

But Elvis was different.

Between scenes, she’d rush to her dressing room and play his latest recordings.

Her conversations were sprinkled with “Elvis this,” and “Elvis that.”

Her bitterest disappointment was that he was in Europe, and there was no chance for her to meet him and get his autograph.

Laurence Olivier (“Uncle Larry”) would take her to lunch—but as much as she adored “Uncle Larry,” he couldn’t compare with Elvis.

He was her very own first love.

Life was quiet that first summer in Hollywood. Outside of the Disney studios, she was virtually unknown. She was taken to Disneyland, and had a perfectly marvelous time.

The only stares that greeted the “party” were aimed at her guide—a man by the name of Walt Disney.

HER ONLY PROBLEM was that she was shooting up like a reed, and there was a race against time to finish the picture before she “outgrew” the role. Within a year she had shot up to 5‘ 3”—a good inch taller than Juliet.

“Oh, my dear!” she would write, “if I keep growing any taller, I shall be taken for your older sister.”

When Pollyanna was completed the entire family with the exception of Juliet were re-united in Tobago where John was making Swiss Family Robinson. Tobago was like a vacation—even if there was school. In Tobago Hayley and Jonathan went to a negro school and the only other white pupil was the brother of Janet Munro who worked with John. But doing their lessons in so many different places like this was more fun than work.

If Hayley had been sensational in Tiger Bay, her “Pollyanna” was phenomenal. Wrote one critic:

“Young Miss Mills’ contribution to its (Pollyanna’s) unexpected delights is fresh and funny and beguiling and utterly unspoiled. Mawkish, gooey sentimentality has no place in her performance. It is mercifully free also of the “cute brat” mannerisms which have marred the work of so many screen juveniles in the past including some who have become box-office sensations. We predict Hayley will become the greatest box-office sensation of them all.”

With the release of Pollyanna came recognition—and problems.

It was great fun to be asked for autographs—and all that—but for reasons Hayley still can’t understand, people insisted upon talking to her as if she was four years old instead of a budding young lady of fourteen.

“Ooooooh you cute little thing,” they’d say. “Wrinkle your ittsy bitsy little nose for us like you did in the movie.”

It infuriated her—and made her just a little ill, and if she wrinkled her nose it was for reasons other than anticipated.

“Talking down” to Hayley is akin to talking down to Albert Einstein.

And yet, she can in no way be termed precocious.

Mary Mills has brought her two daughters up with rare intelligence and understanding.

She feels Hayley is still “too young” to wear make-up, and “date,” but there is nothing she has “kept from her.”

HAVING BEEN BROUGHT UP ON A FARM since babyhood, Hayley learned about the birds and the bees from the birds and the bees and the cows and the horses.

When she was twelve, Mrs. Mills translated this knowledge into human terms. She didn’t, however, say, “You must never do this or that or the other thing.” Instead she sensibly explained the dangers of premarital sex and left it at that—with complete confidence in both her daughters’ intelligence and sense of morality.

“I wanted,” she said, “my children to know about these things normally and naturally from me. I didn’t want them to learn about sex behind a back fence, at school, or from uninformed companions. Too many mothers make that mistake.”

When Hayley expressed a curiosity about “cocktails,” Mrs. Mills let her taste one knowing full well she’d hate it—as she did. Now—even on special occasions, Hayley is barely able to take a sip of diluted wine with the family. The problem of smoking too soon was handled in the same way.

Although she has many close girlfriends both in England and now in Hollywood, Hayley’s closest “friend” is, of course, her sister Juliet.

The four-year age difference between them doesn’t seem to matter, nor are Hayley and Juliet jealous of each other.

“People ask me all the time,” says Juliet, “or at least want to ask me, if I’m jealous of Hayley, because I’ve been acting all my life, and she became a big star within a year.

“Of course, I’m not. How can I be? I love my sister. Besides Hayley is a cinema star and I’m fundamentally a stage actress—so there is no competition between us.”

“There never has been any really. Not because of the four-year difference in our ages—because we do not take notice of that really—but because we’re different.

“Hayley is pixie and I’ve never been pixie—and she is quite good for me. She gets angry and gets into a terrible fit and it lasts just a minute. When I get angry—I brood—unless Hayley is there to snap me out of it. And we’re forever playing marvelous pranks on one another. She’s more my friend—than just a sister.

“We used to share the same bedroom—but now that we are both working and keeping such different hours, we have our own rooms. Except on the weekends. Then she comes into my room to spend the night—and we talk forever—about millions of things. Not too much about boys yet though. I don’t want to get married for a long, long time—and Hayley hasn’t discovered boys. But we talk about everything that has happened to us—and laugh and just have a marvelous time. I know we are different from most ‘average’ teenagers in this country because of the way we have been brought up—and our careers, and travels, but in our basic interests and habits, we’re not all that different really. Except I do hope you won’t have us sounding like Sandra Dee. It’s not that Hayley and I don’t like Sandra Dee, except that when you read about her it all comes out ‘too much,’ don’t you think?”

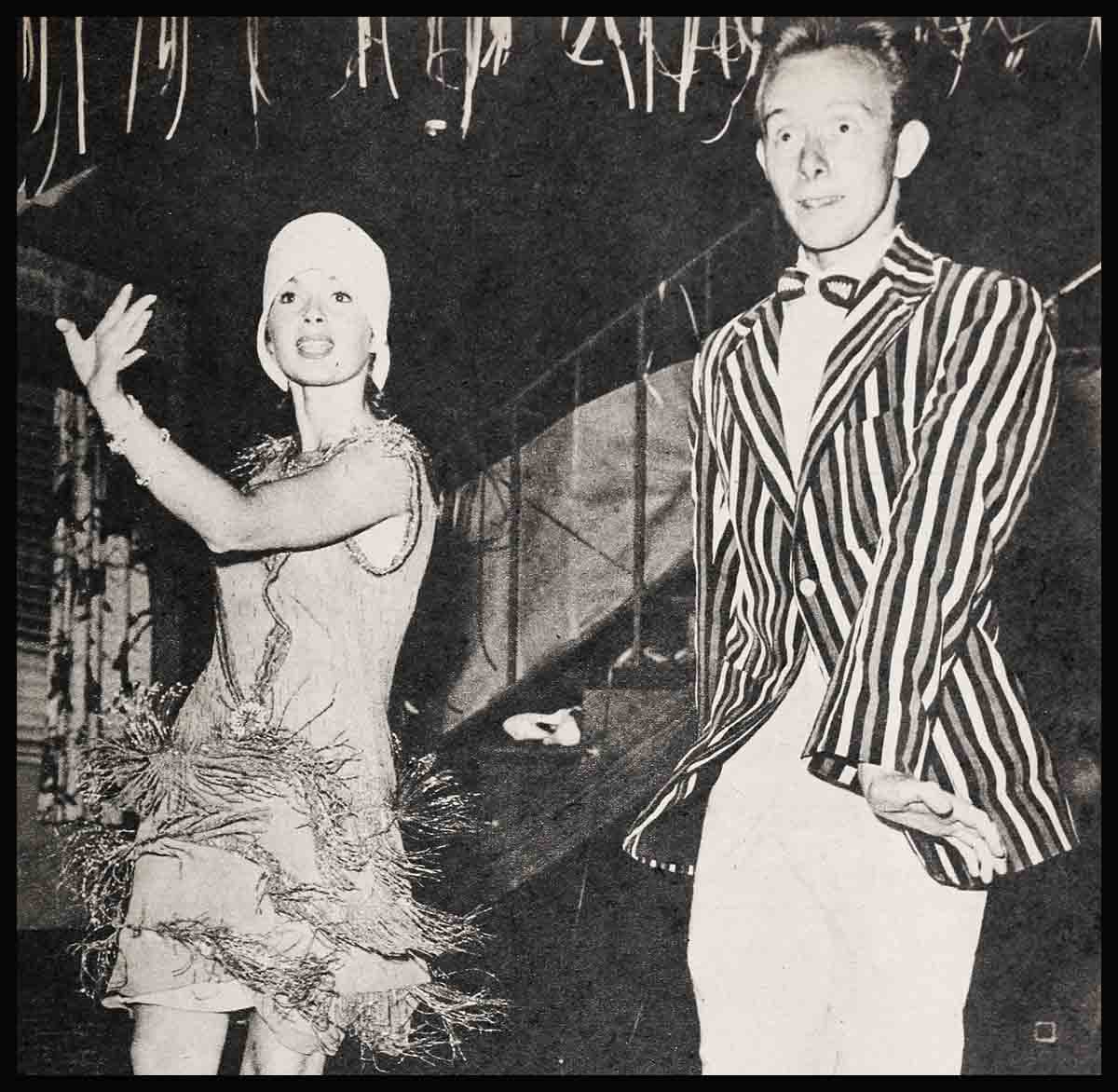

THIS PAST SUMMER in Hollywood when Hayley was working on her newest picture, tentatively titled Bluejeans And Petticoats (in which she plays identical twins) was one of the pleasantest for all the Mills—and there were a dozen weekends for Hayley and Juliet to get together for girl-talk.

But of them all, one particularly stands out.

Hayley and Juliet were in absolute hysterics over the offer Hayley received to play Lolita. An offer, incidentally that was promptly rejected . . . for many reasons, not the least of them being that Hayley had to return home to school.

But in the midst of their frolicking, Hayley turned suddenly very serious.

“Juliet?” she asked in all earnestness. “What do you think it would be like to be a flop?”

Juliet thought for a while—but never having been a flop or in one, was stumped for an answer.

“Oh, I don’t know, Hayley,” she answered. “I really can’t say. But I should imagine that it would be frightfully depressing.”

“Yes. I would imagine that it would be,” Hayley echoed pensively.

“Oh, Juliet, you don’t think I’m just a flash-in-the-pan, do you?”

We should say not!

THE END

Hayley’s next starrer is Buena Vista’s PETTICOATS AND BLUEJEANS.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1960

No Comments